I finally broke down and did it. I watched the Help. I’d been trying to hold out until I’d had a chance to get my hands on a copy of the book, but that just hadn’t happened yet. The Library copy was always checked out, too. Sunday night we were going to curl up on the couch, eat our dinner just us {special moment — waiting till the kids are in bed to have a quiet meal and not have to simultaneously feed yourself and somebody else!} and watch a movie. Woop!

We trolled through the tons of movies on iTunes, youtube and Hulu, and after much discussion and deliberation, the Hubs finally said, “Why don’t we watch The Help? I mean it’s at least something you want to see — if we’re going to pay for it, let’s watch something we want to see.” I couldn’t argue with that logic, and I was rather pleased with the choice, so I agreed as fast as I could {before he changed his mind.}

I cried.

I for real cried.

I mean to tell you, I paused the movie to go find more tissues cried.

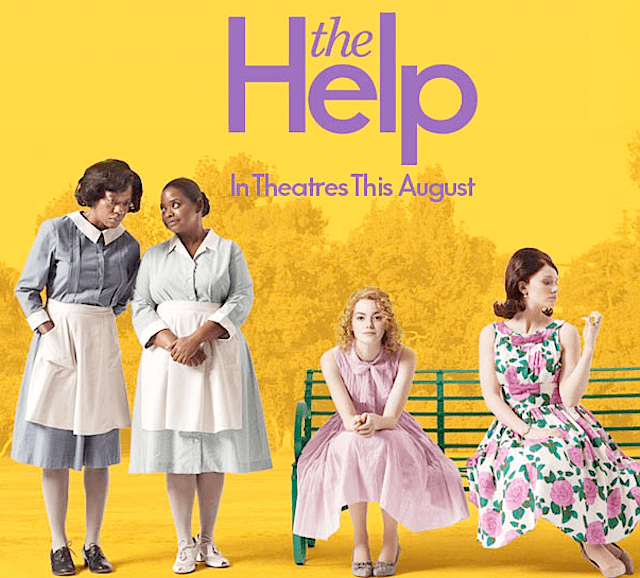

{image via google images}

Afterwards, I thought about all the interesting details, plot lines and unexpected moments, (I almost always ponder a film for at least a week after seeing it) and the next evening, for the first time in our close-to five years of marriage, I cooked fried chicken for dinner.

I think that might somehow be related.

But one interesting lesson the movie immediately brought to heart for me {how similar to the book was it, you friends who’ve read & watched? Did they butcher it?} was drawn from the beautiful relationship Aibileen has with the adorable little toddler she keeps, (and is basically raising) Mae Mobley.

From one of the earliest scenes in the film, you’re introduced to their relationship with Mae Mobley sitting on Aibileen’s lap, repeating these simple sentences:

I is kind.

I is smart.

I is important.

As the story developed and you began to see Mae Mobley’s (nearly non-existent) relationship with her mother, you began to ponder how much thought Aibileen might’ve put into the words she’d chosen to speak over Mae Mobley’s life from such a tender age.

{In case you aren’t familiar with the story, Mae Mobley’s mother, Elizabeth, seems unable to accept her daughter, and it seems that part of the reason is because she does not think she is pretty enough — she is pudgy and it seems her Mama finds her homely. Instead of praising Mae Mobley for her successful potty training, Elizabeth publicly disciplines her for climbing up onto a potty that has been placed on someone’s front yard as a result of a prank. ‘Keeping up appearances’ is consistently more important than relationship — and her child is not helping her ‘keep up appearances,’ so she has to reject her. Aibileen discusses the problematic relationship between Mae Mobley and her mother when she talks about her experiences as a black woman raising white children. (She concludes that Elizabeth should not have babies.)}

The interesting lesson this snippet of the bigger story drew me to think about was first, considering the importance of questioning who tells you who you are, and second, giving great thought to the words you choose to speak over your own children.

As a toddler, I would imagine Mae Mobley could only conclude that her mother’s neglect and disinterest in a relationship with her had to do with her own inadequacy. She wasn’t pretty enough, or smart enough, or basically important enough to warrant being picked up more than once a day or having her diaper changed before ‘the help’ arrived to take care of that chore.

You’d think your own mother would be a good source for information related to what you ought to believe about yourself — who you are and who you have the potential to become. But in this broken world, it’s sometimes the people who are closest to us who speak words to us that give us anything but life. Those words we carry around for decades that tell us we’re not good enough, we’re not smart enough, we’re not capable of succeeding — they often come from the mouths of the people we love the most. Sometimes they’re flippant and thoughtless comments, and sometimes they are intentionally hurtful statements. Either way, they tend to have a profound impact on us — and if we’re not careful, we can carry those words from cradle to grave, letting them tell us our can’s and our can’ts.

I heard the story of a girl who happened to be standing near her pastor at church one Sunday. After the congregation had sung a few worship songs, he turned to her, having never heard her sing before, and said, “You have an absolutely beautiful singing voice!”

She laughed and said, “No I don’t, I’m a terrible singer!”

He quickly asked, “Who told you that?”

“My mother. When I was a little girl, I walked into the kitchen singing one day, and I remember her turning to me and saying, ‘Stop singing! You have the worst singing voice in the world!'”

Perhaps this was just a flippant comment from a dead-on-her-feet mother with the pressures of life crowding her in. But the words planted a seed. The words left a scar. And the world was robbed of enjoying a beautiful voice for many years, because of the seed took root.

The fact that God just spoke the world into existence spurs me not to forget the power of words.

Could there be some words from your past that you need to let go of?

Or does anything you’ve said to someone else come to mind that you want to ask forgiveness for?

The irony is that the wisest words being spoken over little Mae Mobley’s life were the ones from a woman who didn’t have the privilege of an extended eduction. Don’t let the grammatical errors distract you from the beauty of the message. {Want to scroll back up and read it again?}

Who speaks words of life to you?

xCC

I create resources to help people find deeper, more meaningful relationships with God through pursuing, pondering, and prayer. The "Shop" link above will take you to the home of many of the lovely resources I’ve created to help you keep walking one day deeper with Jesus.

I create resources to help people find deeper, more meaningful relationships with God through pursuing, pondering, and prayer. The "Shop" link above will take you to the home of many of the lovely resources I’ve created to help you keep walking one day deeper with Jesus.

It’s funny how you pick up different things from a movie. I also love that daily routine Aibileen did with Mae Mobley. But what jumped out at me was a woman who had suffered post-natal depression (Elizabeth) and probably didn’t get the support she needed because she was expected to ‘keep up appearances’. How many educated women I have seen in that trap struggling to bond with a child after PND. At points I could see the envy from Elizabeth seeing how Aibileen could bond with Mae Mobley in a way she wanted to but just didn’t know how.

And then in contrast you see the depression that Aibileen suffers after the loss of her son – her friends know, recognise it and they support her through it. They keep her going. They don’t try to brush it under the carpet or ignore it.

The real thing is education is often not taught in schools. It is taught in life. And Aibileen had a real good degree in the University of Life – in fact I reckon she lived so well in the face of adversity that she gets a 1st Class honours degree. 🙂

Spot on CC! I think that this is one of the most crucially important challenges of parenthood!

Hello, I have read the book AND watched the movie (just once, but can’t wait to see it again). The book is outstanding and I hope you can read it soon. (does your Library let you reserve books? 🙂

I was happy to see that the film stayed fairly true to the book – there were a few changes but they didn’t take away from or alter the message/focus. In other words, the changes didn’t bother or offend me 🙂 And I can get pretty worked up about stuff like that!

Words of life: often spoken to me by friends who I am walking the Path along side of – and of course, when the Holy Spirit lifts words from the pages of my Bible and pretty much shines a flashlight on them. And I am so grateful.